Rain and floods: How global heating could alter Nordic summers

Last month was one of the wettest Augusts on record in Norway, Sweden and Denmark. We asked three climate scientists if climate change could make this weather normal in future.

Denmark's state forecaster DMI has declared July the wettest since records began in 1874, with more than double the normal rainfall, while August was the wettest for nine years,

August in Norway was the fourth wettest since the country started taking records in 1900, with new rainfall records set at over 100 weather stations, according to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

And in Sweden, weather forecaster SMHI announced that August had set rainfall records at 24 weather stations, twelve of which had never recorded as much rain in any month ever, regardless of the season.

So should we expect this summer's cool, very rainy weather to become the norm going forward, now that climate change is disrupting weather patterns?

According to Ketil Tunheim, a researcher at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, we probably shouldn't.

"Generally, we expect the weather in Norway to become wetter and wilder, and we've seen this trend already. However, that is a slow trend, and events like we've had recently are extreme anomalies even compared to that development," he told The Local.

"I haven't seen a full analysis of the rainfall events we've had in August, but we don't expect this to happen many times in a century. So I don't think the torrential rains of this summer will become normal summer events any time soon."

"My gut feeling is that if scientists eventually did an analysis of this summer, they would say that it was still within the range of normal weather," said Thorsten Mauritsen, the Danish climate scientist and Stockholm University professor. "It's been an unusually wet summer and cold, but I don't know if it would qualify as extreme."

So what does climate science predict about Nordic summers?

According to Mauritsen, the rule of thumb is that for every one percent rise in temperature, seven percent more water evaporates into the atmosphere, all or most of which must fall somewhere as rain.

"What we expect is more extreme, torrential precipitation combined with drier, warmer conditions at other times," he said.

This does not mean the Nordic countries will always be rainier, and long dry spells are likely to happen in summer as well as wet ones.

"You will have some summers, like 2018, where we are constantly under a high and it gets really dry and warm, and we get a lot of problems with forests fires. And then there will be other summers, like this one, where we happen to be in a low pressure region and then we will get a lot of rain," Mauritsen said.

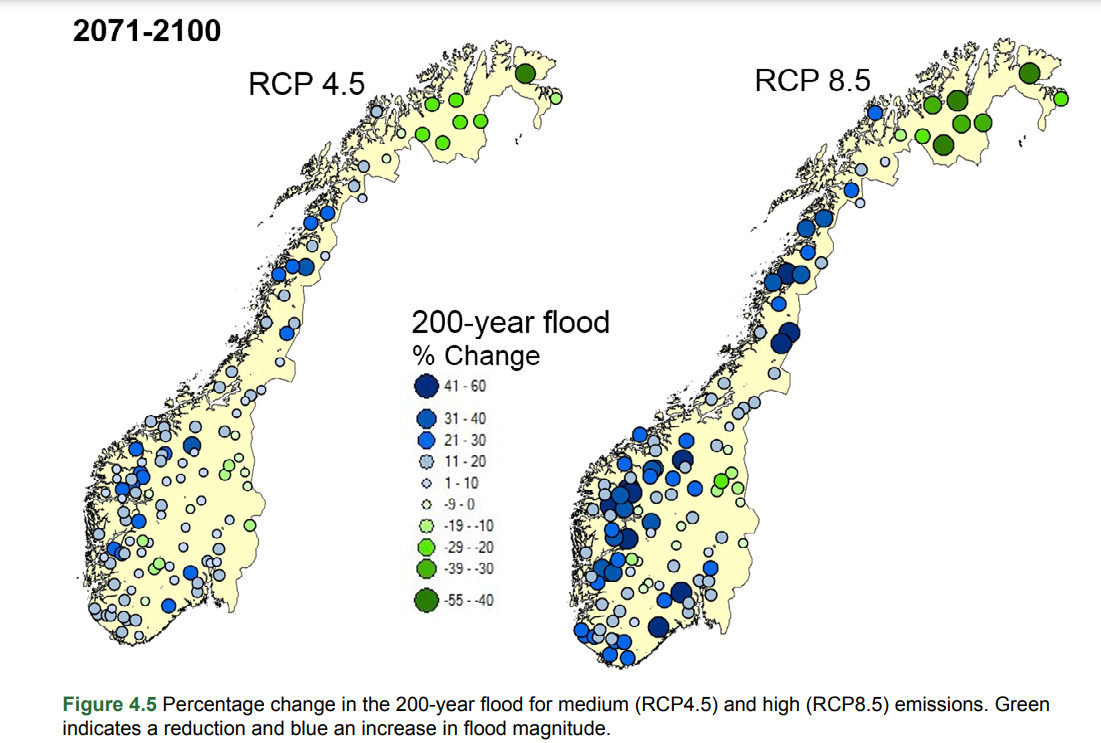

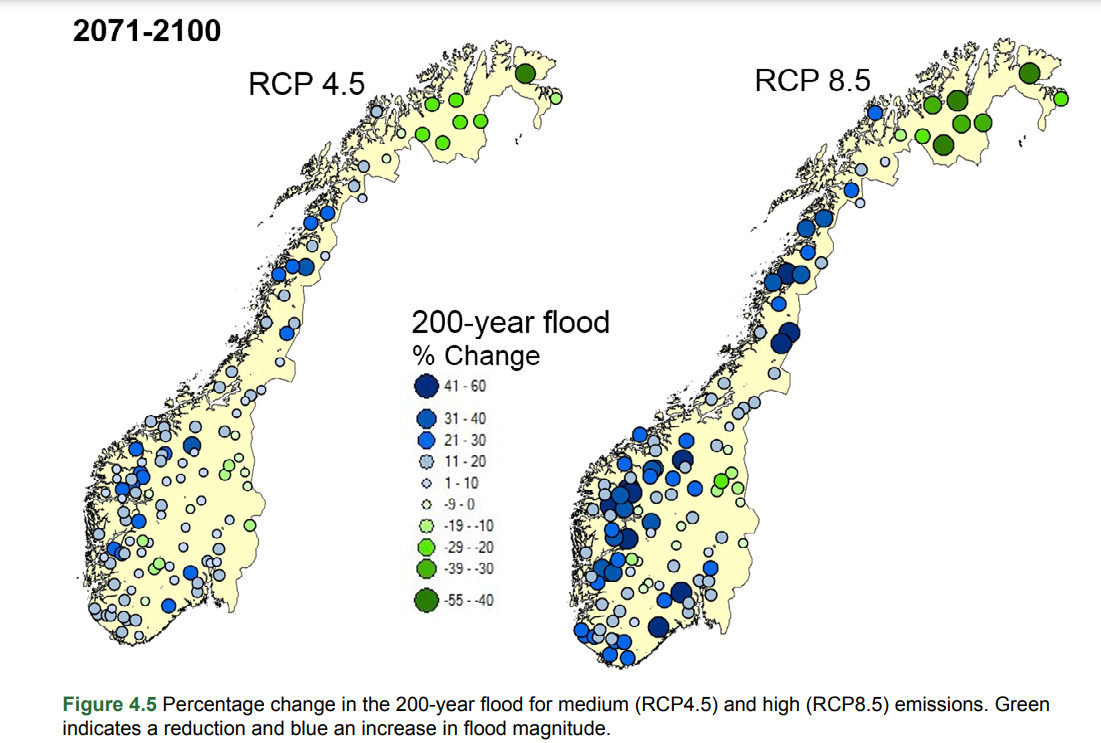

The Norwegian Meteorological Institute's predictions for the scale of future floods in medium and high emissions scenarios do, however, show an increased scale in many of the same areas badly hit by Storm Hans last month.

The percentage change in the likelihood of a 200-year flood in different parts of Norway between 2075 and 2100. Photo: Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

"In the coming years, we must be prepared for more of the same: generally warmer and wetter in most places in Norway. On top of this, will come extreme events such as heavy rainfall in line with what "Hans" brought," Frode Stordal, professor emeritus and climate scientist at the University of Oslo, told NRK.

Sweden's SMHI expects rainfall to increase by an average of 8mm a month across Sweden between 2041 and 2070 in a scenario where there is no reduction in emissions, with Northern Sweden the worst affected area.

Will we see a repeat of this summer's disruption?

This summer's rainfall has done an unusual amount of damage, washing soil from beneath a railway track in Sweden and derailing a train, and leading to a railway bridge collapsing and a dam overflowing in Norway.

Mauritsen suspects that this will be something we will see more of, as the natural world, the landscape, human settlements and infrastructure all experience heavier rainfall than they are adapted to.

"We've been building houses and roads and sewers and so on for hundreds of years and they are a certain size because experience says that's going to work. But then suddenly we get more precipitation and it doesn't work anymore," he said.

"So you get a flood in an area around a train track and it's washed away, or there is this dam. I think we can we can certainly conclude from this summer that we are more vulnerable than we maybe had thought, and that we will see this more frequently in the future, not every year, but maybe every 10 years or so."

Could we get a surprise?

Peter Ditlevsen, a Professor at Copenhagen University's Nils Bohr Institute, made headlines in July when he published a paper stating that the Atlantic ocean currents responsible for bringing a warmer water climate to the UK, Ireland, Iceland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden, might be disrupted as early as 2025.

If this were to happen, it would undermine all the predictions of a warmer, wetter climate for northern Europe.

"It's a very scary scenario, because these are permanent, large changes to the local climate," Ditlevsen told The Local.

Without the warm waters from the US Gulf, temperatures in Denmark, Sweden and Norway would be similar to those in northern Canada or Alaska, becoming about ten degrees colder in the winter and maybe 5 degrees colder in the summer.

"It's probably the winters that will be coldest, because what makes winters mild is the relatively warm waters in the Atlantic," he said.

He pushed back at those who had reported that his study as saying the Atlantic currents would stop as early as 2025, saying his preference now was to say that there was "a high probability that this could happen mid century".

"You could have a three degree change per decade over three decades," he said, adding that the last time this Atlantic current had stopped, during the last ice age, the switch had happened in a single decade.

Mauritsen, however, dismissed the study, saying the likelihood of the current being disrupted was "highly overestimated" by Ditlevsen and his colleagues.

Comments

See Also

Denmark's state forecaster DMI has declared July the wettest since records began in 1874, with more than double the normal rainfall, while August was the wettest for nine years,

August in Norway was the fourth wettest since the country started taking records in 1900, with new rainfall records set at over 100 weather stations, according to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

And in Sweden, weather forecaster SMHI announced that August had set rainfall records at 24 weather stations, twelve of which had never recorded as much rain in any month ever, regardless of the season.

So should we expect this summer's cool, very rainy weather to become the norm going forward, now that climate change is disrupting weather patterns?

According to Ketil Tunheim, a researcher at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, we probably shouldn't.

"Generally, we expect the weather in Norway to become wetter and wilder, and we've seen this trend already. However, that is a slow trend, and events like we've had recently are extreme anomalies even compared to that development," he told The Local.

"I haven't seen a full analysis of the rainfall events we've had in August, but we don't expect this to happen many times in a century. So I don't think the torrential rains of this summer will become normal summer events any time soon."

"My gut feeling is that if scientists eventually did an analysis of this summer, they would say that it was still within the range of normal weather," said Thorsten Mauritsen, the Danish climate scientist and Stockholm University professor. "It's been an unusually wet summer and cold, but I don't know if it would qualify as extreme."

So what does climate science predict about Nordic summers?

According to Mauritsen, the rule of thumb is that for every one percent rise in temperature, seven percent more water evaporates into the atmosphere, all or most of which must fall somewhere as rain.

"What we expect is more extreme, torrential precipitation combined with drier, warmer conditions at other times," he said.

This does not mean the Nordic countries will always be rainier, and long dry spells are likely to happen in summer as well as wet ones.

"You will have some summers, like 2018, where we are constantly under a high and it gets really dry and warm, and we get a lot of problems with forests fires. And then there will be other summers, like this one, where we happen to be in a low pressure region and then we will get a lot of rain," Mauritsen said.

The Norwegian Meteorological Institute's predictions for the scale of future floods in medium and high emissions scenarios do, however, show an increased scale in many of the same areas badly hit by Storm Hans last month.

"In the coming years, we must be prepared for more of the same: generally warmer and wetter in most places in Norway. On top of this, will come extreme events such as heavy rainfall in line with what "Hans" brought," Frode Stordal, professor emeritus and climate scientist at the University of Oslo, told NRK.

Sweden's SMHI expects rainfall to increase by an average of 8mm a month across Sweden between 2041 and 2070 in a scenario where there is no reduction in emissions, with Northern Sweden the worst affected area.

Will we see a repeat of this summer's disruption?

This summer's rainfall has done an unusual amount of damage, washing soil from beneath a railway track in Sweden and derailing a train, and leading to a railway bridge collapsing and a dam overflowing in Norway.

Mauritsen suspects that this will be something we will see more of, as the natural world, the landscape, human settlements and infrastructure all experience heavier rainfall than they are adapted to.

"We've been building houses and roads and sewers and so on for hundreds of years and they are a certain size because experience says that's going to work. But then suddenly we get more precipitation and it doesn't work anymore," he said.

"So you get a flood in an area around a train track and it's washed away, or there is this dam. I think we can we can certainly conclude from this summer that we are more vulnerable than we maybe had thought, and that we will see this more frequently in the future, not every year, but maybe every 10 years or so."

Could we get a surprise?

Peter Ditlevsen, a Professor at Copenhagen University's Nils Bohr Institute, made headlines in July when he published a paper stating that the Atlantic ocean currents responsible for bringing a warmer water climate to the UK, Ireland, Iceland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden, might be disrupted as early as 2025.

If this were to happen, it would undermine all the predictions of a warmer, wetter climate for northern Europe.

"It's a very scary scenario, because these are permanent, large changes to the local climate," Ditlevsen told The Local.

Without the warm waters from the US Gulf, temperatures in Denmark, Sweden and Norway would be similar to those in northern Canada or Alaska, becoming about ten degrees colder in the winter and maybe 5 degrees colder in the summer.

"It's probably the winters that will be coldest, because what makes winters mild is the relatively warm waters in the Atlantic," he said.

He pushed back at those who had reported that his study as saying the Atlantic currents would stop as early as 2025, saying his preference now was to say that there was "a high probability that this could happen mid century".

"You could have a three degree change per decade over three decades," he said, adding that the last time this Atlantic current had stopped, during the last ice age, the switch had happened in a single decade.

Mauritsen, however, dismissed the study, saying the likelihood of the current being disrupted was "highly overestimated" by Ditlevsen and his colleagues.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.