The Swede, the Dane and the Norwegian: who's the butt of Nordic jokes?

The Swedes joke about the Norwegians, the Norwegians about the Swedes, and the Danes about both, or perhaps neither. But the mostly friendly joshing between Scandinavian countries is more recent than you might think.

In Sweden, they're Norgehistorier ("Norway stories"), in Norway Svenskevitser ("Swede jokes"). The Danes tend to reserve their Aarhus-vittigheder for people from the country's second biggest city.

These jokes are the equivalent of Irishman jokes in England or Polish jokes in the US. Indeed, they're very often the exact same jokes with just the nationality changed.

According to the Swedish folklorist Bengt af Klintberg, rather than having roots deep in history, these particular jokes are of a surprisingly recent vintage, the relic of a trend that swept the world in the 1970s.

"This was an international joke fad that started actually in America," he told The Local. "The American 'Polack jokes' spread to Europe, and in England, they were talking about Irishmen, in France, Belgians, and in Germany, about people from Austria. Very often the neighbouring country is accused of being stupid, and both the jokers and the the victims know that this is not true. You should not take them seriously."

Who do Europeans joke about the most?

- pic.twitter.com/aDfbnLt9X9

— Amazing Maps (@Amazing_Maps) October 26, 2016

The joke war

When these jokes started becoming popular in the early 1970s, tabloid newspapers picked up on the fad, with the Expressen newspaper reporting at the start of 1975 that "all the jokes now are about crazy Norwegians", and printing a number of examples.

Norway's Verdens Gang (VG) tabloid responded by asking readers to send in jokes about Sweden, and Expressen hit back by declaring a so-called Vitsekriget.

"They called it a 'joke war' between Sweden and Norway," af Klintberg remembers. "Everybody felt it was quite all right to tell jokes about stupid Swedes and stupid Norwegians, because we all knew that we are neighbours and we like each other, and that this was just some sort of teasing."

It was a high-profile, if short-lived, cultural phenomenon.

VG collaborated with Expressen to have its readers' Svenskevitser published in Sweden. Expressen collected a list of 1,000 Norgehistorier which it sent to be archived by the Nordic Museum in Stockholm, while the equivalent museum in Norway archived 300 Svenskevitser.

On May 30th, 1975, Arve Opsahl, the Norwegian actor and comedian appointed as "general" to lead the Norwegian side, signed a peace agreement with the comedian Jan "Moltas" Erikson, who represented the Swedes, officially ending the hostilities.

The jokes, however, lived on. While perhaps not as common as they were in their heyday, schoolchildren in both countries still learn them, and you can find online lists of Norgehistorier and Svenskevitser, and children's books full of favourites (see here and here).

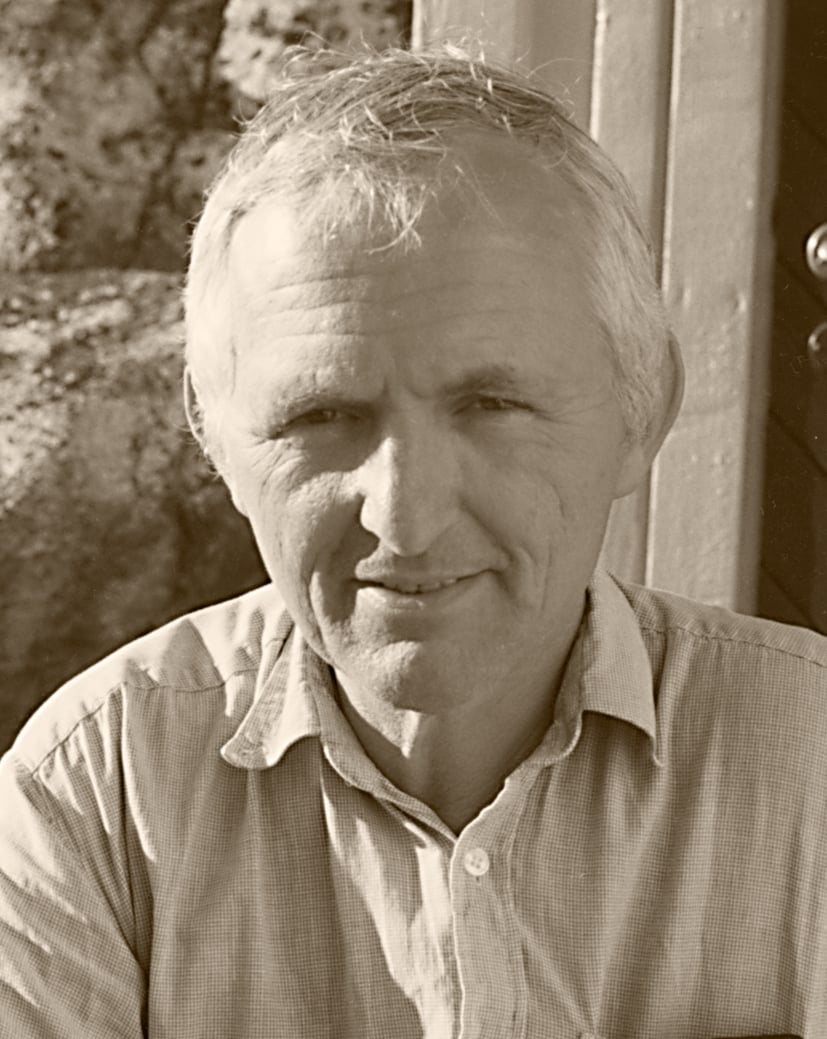

The Swedish folklorist and artist Bengt af Klintberg. Photo: Atlantis Bokförlag

Examples of Svenskevitser

Here are some examples of (typically quite unfunny) Svenskevitser and Norgehistorier, with an English translation.

Hvorfor har svenskene med seg en bildør i ørkenen?

slik at de kan åpne vindue viss det blir varmt.

Why do Swedes always take a car door into the desert?

So that they can wind down the window if it gets too hot.

Det var en gang en svenske som var ute og kjørte bil da en nyhetssending kom på radioen.

Reporteren: Vi melder om at en bil kjører mot kjøreretningen på E6 i nord-gående retning.

Svensken: ÉN?! Det er jo flere hundre av dem!

There was once a Swede out driving a car when there was a warning sent out on the radio: We are warning that there is a car driving in the wrong direction on the E6 in a northbound direction.

One? exclaimed the Swede. "There are bloody hundreds of them!"

Examples of Norgehistorier

Vad kallas smarta personer i Norge? Turister

What are clever people called in Norway? Tourists.

Två norska poliser hittade en död man framför en Peugeot

Hur stavar man till Peugeot?

Jag har ingen aning. Vi lägger honom framför en Fiat i stället!

Two Norwegian policeman found a dead man in front of a Peugeot.

"How do you spell Peugeot?" says one.

"No idea," says the other. "Let's leave him in front of a Fiat instead."

The Swede, the Dane, and the Norwegian

There's a variety which combines all three Scandinavian nationalities, a little like the "Englishman, Irishman and a Scotsman" jokes popular in the UK, with the Norwegian the butt of the joke in Sweden and the Swede in Norway.

Sometimes these, like other Norgehistorier or Svenskevitser, settle with characterising the neighbouring country as stupid, like this one:

Det var en gang at en svenske, danske og en nordmann var ute i skogen og gikk tur. Nordmannen var døv, dansken var blind og svensken var lam fra livet og ned og satt i rullestol. Etter en stund kom de til en magisk grotte i skogen, der hver og en av dem kunne få oppfylt ett ønske. Først gikk nordmannen inn. Etter en stund kom han ut og utbrøt lykkelig: "Gutter, jeg kan høre!" Etter ham gikk dansken inn og kom ut like fornøyd: "Gutter, jeg kan se!" Sist men ikke minst trillet svensken inn. Etter en stund kom han ut og ropte: "Kolla grabbar, nya hjul!"

A Swede, a Dane and Norwegian were out hiking in the woods. The Norwegian was deaf, the Dane blind and the Swede disabled and in a wheelchair. They came to a magical cave where each of them could make one wish. First the Norwegian went in. "Lads, I can hear!" he exclaimed. Then the Dane. "Lads, I can see!" Then finally, in went the Swede. After a while he came out and shouted. "Look guys, new wheels!"

But they can also sometimes refer to national stereotypes, such as this one, which is used in the introduction of Joking Relationships and National Identity in Scandinavia, an article on Scandinavian jokes published by Copenhagen University sociologist Peter Grundelach.

"Two Danes, two Finns, two Norwegians, and two Swedes are shipwrecked and cast upon a deserted island. By the time they are rescued the Danes have formed a co-operative, the Finns have chopped down all the trees, the Norwegians have built a fishing boat, and the Swedes are waiting to be introduced."

Grundelach took the joke from The Scandinavians, a book by Time Magazine correspondent Donald S Connery, who explains the joke (which shows signs of Danish origin) as follows:

"Among the Scandinavians themselves...it is popularly held that the Danes are fun-loving, easygoing, shallow, shrewd, not altogether sincere and not inclined to too much exertion; the Norwegians are sturdy, brave, but a little too simple and unsophisticated...the Swedes are clever, capable, reliable, but much too formal, success-ridden and neurotic."

Jokes on real national stereotypes

The Scandinavians was published in 1966, so that joke predates the Joke War by nearly ten years, and according to af Klintberg, the relatively few jokes Scandinavians made about each other before this time tended to build on stereotypes, such as that Norwegians are ridiculously nationalistic (which annoyed the Swedes and Danes, who had both controlled Norway in the past), Danes are workshy and pleasure-seeking, and Swedes are uptight and moralistic.

"They dislike the Swedish for being the big brother in the Scandinavian context and also that always try to be a moral example," af Klintberg says about the Danes. Swedes on the other hand, he adds, tend to slightly envy the Danes for being more fun-loving.

"We talk about 'the Danish smile', det danske smil," he said. "And this shows that the Swedes sometimes would like to be a little more like the Danes, who do not take alcohol as seriously as we do."

On the other hand, Danes, with their more continental habits of alcohol consumption, once laughed at Swedes for rolling about drunkenly after coming off the boat from Malmö or Helsingborg.

"What's the difference between Swedes and mosquitoes?" goes a Danish joke Grundelach cites in his article. "Mosquitoes are only annoying in the summertime."

Danes and Swedes' jokes about the Norwegians tend to revolve around their excessive national pride, and also around their simplistic, literalistic use of language.

"A joke that was told already at the turn of the last century is about a Norwegian who comes to Copenhagen and looks at the Rundetårn [a famous round tower in the city], and he walks around it and then says: 'In Norway, we have towers that are much rounder'," af Klintberg reports.

Literalistic language

Finally, both Danes and Swedes joke about what they see as the overly literalistic compound words which they imagine exist in Norwegian, with a collection of words in skämtnorska, or joke Norwegian, sometimes expressed in joke form, such as this Danish example, which literally translates the lim in Limfjord, the fjord in northern Jutland as "glue":

Hvad kalder nordmændende Limfjorden? Klisterkanalen.

"What do the Norwegians call the Limfjord? The glue canal."

Danes and Swedes both like to claim tongue-in-cheek that the Norwegian word for shark is kjempetorsk, which means "giant cod", or that the word for "popcorn" is eksploderende majs, literally "exploding maize".

For af Klintberg, this is a way to hit back at the efforts writers such as Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson made at the end of the 19th century to establish Norwegian as a literary language separate from Danish.

"There has been a language war in Norway. The goal was to have a real Norwegian language, not a language that was a kind of dialect of Danish."

So, finally, why does no one joke about the Danes?

In his article, Grundelach, points out the strange asymmetry in Scandinavian humour, that while the Norwegians and Swedes joke about each other, and the Danes a little about both Swedes and Norwegians, no one seems to joke much about the Danes.

As a Dane, he could have argued that his own people were more respected or liked. But he instead comes to the opposite conclusion, citing a survey from 1990 showing that Norwegians and Swedes tended to prefer one another to the Danes.

"These data indicate that Norwegians and Swedes feel mutually closer than they do to the Danes, and this may at least partially explain the reciprocal (symmetrical) nature of the joke-telling between the two countries," he explains. "Denmark seems to be a less significant country for the other two nations, which may explain why there are few jokes about the Danes."

Comments

See Also

In Sweden, they're Norgehistorier ("Norway stories"), in Norway Svenskevitser ("Swede jokes"). The Danes tend to reserve their Aarhus-vittigheder for people from the country's second biggest city.

These jokes are the equivalent of Irishman jokes in England or Polish jokes in the US. Indeed, they're very often the exact same jokes with just the nationality changed.

According to the Swedish folklorist Bengt af Klintberg, rather than having roots deep in history, these particular jokes are of a surprisingly recent vintage, the relic of a trend that swept the world in the 1970s.

"This was an international joke fad that started actually in America," he told The Local. "The American 'Polack jokes' spread to Europe, and in England, they were talking about Irishmen, in France, Belgians, and in Germany, about people from Austria. Very often the neighbouring country is accused of being stupid, and both the jokers and the the victims know that this is not true. You should not take them seriously."

Who do Europeans joke about the most?

— Amazing Maps (@Amazing_Maps) October 26, 2016

- pic.twitter.com/aDfbnLt9X9

The joke war

When these jokes started becoming popular in the early 1970s, tabloid newspapers picked up on the fad, with the Expressen newspaper reporting at the start of 1975 that "all the jokes now are about crazy Norwegians", and printing a number of examples.

Norway's Verdens Gang (VG) tabloid responded by asking readers to send in jokes about Sweden, and Expressen hit back by declaring a so-called Vitsekriget.

"They called it a 'joke war' between Sweden and Norway," af Klintberg remembers. "Everybody felt it was quite all right to tell jokes about stupid Swedes and stupid Norwegians, because we all knew that we are neighbours and we like each other, and that this was just some sort of teasing."

It was a high-profile, if short-lived, cultural phenomenon.

VG collaborated with Expressen to have its readers' Svenskevitser published in Sweden. Expressen collected a list of 1,000 Norgehistorier which it sent to be archived by the Nordic Museum in Stockholm, while the equivalent museum in Norway archived 300 Svenskevitser.

On May 30th, 1975, Arve Opsahl, the Norwegian actor and comedian appointed as "general" to lead the Norwegian side, signed a peace agreement with the comedian Jan "Moltas" Erikson, who represented the Swedes, officially ending the hostilities.

The jokes, however, lived on. While perhaps not as common as they were in their heyday, schoolchildren in both countries still learn them, and you can find online lists of Norgehistorier and Svenskevitser, and children's books full of favourites (see here and here).

Examples of Svenskevitser

Here are some examples of (typically quite unfunny) Svenskevitser and Norgehistorier, with an English translation.

Hvorfor har svenskene med seg en bildør i ørkenen?

slik at de kan åpne vindue viss det blir varmt.

Why do Swedes always take a car door into the desert?

So that they can wind down the window if it gets too hot.

Det var en gang en svenske som var ute og kjørte bil da en nyhetssending kom på radioen.

Reporteren: Vi melder om at en bil kjører mot kjøreretningen på E6 i nord-gående retning.

Svensken: ÉN?! Det er jo flere hundre av dem!

There was once a Swede out driving a car when there was a warning sent out on the radio: We are warning that there is a car driving in the wrong direction on the E6 in a northbound direction.

One? exclaimed the Swede. "There are bloody hundreds of them!"

Examples of Norgehistorier

Vad kallas smarta personer i Norge? Turister

What are clever people called in Norway? Tourists.

Två norska poliser hittade en död man framför en Peugeot

Hur stavar man till Peugeot?

Jag har ingen aning. Vi lägger honom framför en Fiat i stället!

Two Norwegian policeman found a dead man in front of a Peugeot.

"How do you spell Peugeot?" says one.

"No idea," says the other. "Let's leave him in front of a Fiat instead."

The Swede, the Dane, and the Norwegian

There's a variety which combines all three Scandinavian nationalities, a little like the "Englishman, Irishman and a Scotsman" jokes popular in the UK, with the Norwegian the butt of the joke in Sweden and the Swede in Norway.

Sometimes these, like other Norgehistorier or Svenskevitser, settle with characterising the neighbouring country as stupid, like this one:

Det var en gang at en svenske, danske og en nordmann var ute i skogen og gikk tur. Nordmannen var døv, dansken var blind og svensken var lam fra livet og ned og satt i rullestol. Etter en stund kom de til en magisk grotte i skogen, der hver og en av dem kunne få oppfylt ett ønske. Først gikk nordmannen inn. Etter en stund kom han ut og utbrøt lykkelig: "Gutter, jeg kan høre!" Etter ham gikk dansken inn og kom ut like fornøyd: "Gutter, jeg kan se!" Sist men ikke minst trillet svensken inn. Etter en stund kom han ut og ropte: "Kolla grabbar, nya hjul!"

A Swede, a Dane and Norwegian were out hiking in the woods. The Norwegian was deaf, the Dane blind and the Swede disabled and in a wheelchair. They came to a magical cave where each of them could make one wish. First the Norwegian went in. "Lads, I can hear!" he exclaimed. Then the Dane. "Lads, I can see!" Then finally, in went the Swede. After a while he came out and shouted. "Look guys, new wheels!"

But they can also sometimes refer to national stereotypes, such as this one, which is used in the introduction of Joking Relationships and National Identity in Scandinavia, an article on Scandinavian jokes published by Copenhagen University sociologist Peter Grundelach.

"Two Danes, two Finns, two Norwegians, and two Swedes are shipwrecked and cast upon a deserted island. By the time they are rescued the Danes have formed a co-operative, the Finns have chopped down all the trees, the Norwegians have built a fishing boat, and the Swedes are waiting to be introduced."

Grundelach took the joke from The Scandinavians, a book by Time Magazine correspondent Donald S Connery, who explains the joke (which shows signs of Danish origin) as follows:

"Among the Scandinavians themselves...it is popularly held that the Danes are fun-loving, easygoing, shallow, shrewd, not altogether sincere and not inclined to too much exertion; the Norwegians are sturdy, brave, but a little too simple and unsophisticated...the Swedes are clever, capable, reliable, but much too formal, success-ridden and neurotic."

Jokes on real national stereotypes

The Scandinavians was published in 1966, so that joke predates the Joke War by nearly ten years, and according to af Klintberg, the relatively few jokes Scandinavians made about each other before this time tended to build on stereotypes, such as that Norwegians are ridiculously nationalistic (which annoyed the Swedes and Danes, who had both controlled Norway in the past), Danes are workshy and pleasure-seeking, and Swedes are uptight and moralistic.

"They dislike the Swedish for being the big brother in the Scandinavian context and also that always try to be a moral example," af Klintberg says about the Danes. Swedes on the other hand, he adds, tend to slightly envy the Danes for being more fun-loving.

"We talk about 'the Danish smile', det danske smil," he said. "And this shows that the Swedes sometimes would like to be a little more like the Danes, who do not take alcohol as seriously as we do."

On the other hand, Danes, with their more continental habits of alcohol consumption, once laughed at Swedes for rolling about drunkenly after coming off the boat from Malmö or Helsingborg.

"What's the difference between Swedes and mosquitoes?" goes a Danish joke Grundelach cites in his article. "Mosquitoes are only annoying in the summertime."

Danes and Swedes' jokes about the Norwegians tend to revolve around their excessive national pride, and also around their simplistic, literalistic use of language.

"A joke that was told already at the turn of the last century is about a Norwegian who comes to Copenhagen and looks at the Rundetårn [a famous round tower in the city], and he walks around it and then says: 'In Norway, we have towers that are much rounder'," af Klintberg reports.

Literalistic language

Finally, both Danes and Swedes joke about what they see as the overly literalistic compound words which they imagine exist in Norwegian, with a collection of words in skämtnorska, or joke Norwegian, sometimes expressed in joke form, such as this Danish example, which literally translates the lim in Limfjord, the fjord in northern Jutland as "glue":

Hvad kalder nordmændende Limfjorden? Klisterkanalen.

"What do the Norwegians call the Limfjord? The glue canal."

Danes and Swedes both like to claim tongue-in-cheek that the Norwegian word for shark is kjempetorsk, which means "giant cod", or that the word for "popcorn" is eksploderende majs, literally "exploding maize".

For af Klintberg, this is a way to hit back at the efforts writers such as Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson made at the end of the 19th century to establish Norwegian as a literary language separate from Danish.

"There has been a language war in Norway. The goal was to have a real Norwegian language, not a language that was a kind of dialect of Danish."

So, finally, why does no one joke about the Danes?

In his article, Grundelach, points out the strange asymmetry in Scandinavian humour, that while the Norwegians and Swedes joke about each other, and the Danes a little about both Swedes and Norwegians, no one seems to joke much about the Danes.

As a Dane, he could have argued that his own people were more respected or liked. But he instead comes to the opposite conclusion, citing a survey from 1990 showing that Norwegians and Swedes tended to prefer one another to the Danes.

"These data indicate that Norwegians and Swedes feel mutually closer than they do to the Danes, and this may at least partially explain the reciprocal (symmetrical) nature of the joke-telling between the two countries," he explains. "Denmark seems to be a less significant country for the other two nations, which may explain why there are few jokes about the Danes."

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.