The middle of nowhere: Inside Denmark’s Kærshovedgård deportation camp

About seven kilometers from Bording, a local station in Jutland, I cycled with two friends to Kærshovedgård, the former-prison-turned-deportation facility.

Located near the town of Ikast, Kærshovedgård is one of Denmark’s two ‘departure centres’ (the term ‘expulsion’ is also commonly used, particularly by critics). Around 200 rejected asylum seekers are accommodated at the facility until they decide to leave.

One of the residents of Kærshovedgård, Jamiar, was waiting for us a few meters outside the gate. The security guards checked our IDs and let us in as Jamiar’s visitors. As we walked by, a few people stood around the old buildings of the facility watching us. Jamiar pointed at the buildings to our left.

Surrounded by fences within Kærshovedgård’s own periphery, “this is where people who committed crimes are kept,” he said.

Jamiar told us that Kærshovedgård’s residents go to court when they commit crimes such as stealing food or not reporting their presence in the camp when they are required to.

The residents of Kærshovedgård are adult men and women who have been permanently refused asylum and whose departure deadline has been exceeded, according to a Ministry of Immigration report.

There are different categories for residency in Kærshovedgård. Women and men live in separate buildings, while individuals who have been convicted of crimes stay in separately in buildings surrounded by more fences and surveillance cameras.

We walked a little further, to where Jamiar lives, on the second floor of one of the more modern, grey buildings. The narrow hallway has doors to more than a dozen rooms, one bathroom and one laundry room. “Please take off your shoes,” the sign on Jamiar’s door read.

'Close Kærshovedgård' stickers in Jamiar's room. Photo: Farah Bahgat

The moment we walked in the room, we could smell the Persian spices Jamiar and his roommate keep. Although they are not allowed to cook inside the camp, Jamiar explained he obtained a small stove because he could not eat the food served in the cafeteria.

“The police say we cannot make food here. We can only eat in the cafeteria and it is only Danish food. I respect Denmark but I cannot eat Danish food,” he said.

Jamiar set up the floor for us to eat the Iranian lunch he had prepared for his guests, and his roommate.

“Thank you for coming, we are happy to welcome people, now we have friends from everywhere,” he said.

The Iranian and his neighbours are used to hosting friends and volunteers from different initiatives and NGOs including the Red Cross, which has a building inside the camp where residents can read donated books and clothes and socialise with each other.

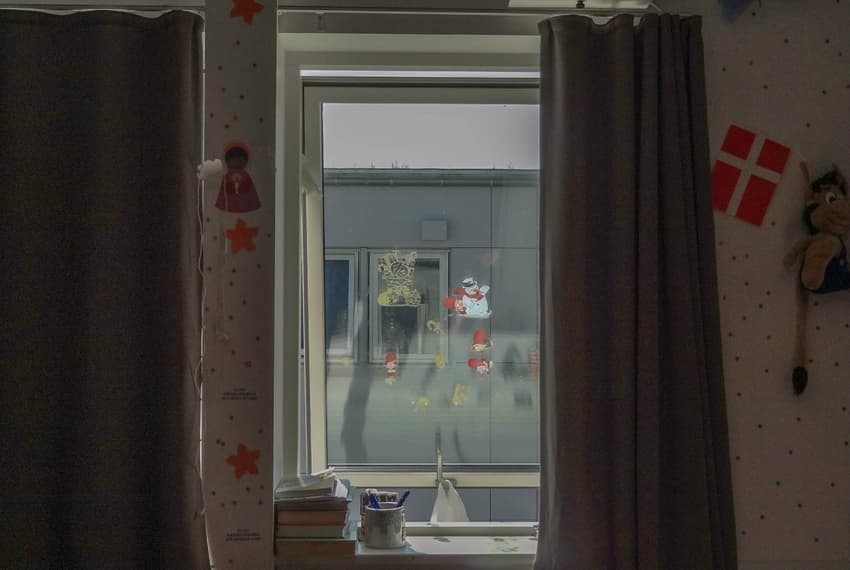

Jamiar's wall. Photo: Farah Bahgat

READ ALSO: One week after minister admitted mistakes, sick asylum seeker returns to Denmark

One initiative, the Solidarity Project, arranges visits to Kærshovedgård, as well as trips for asylum seekers to other cities in Denmark.

“Our aim is to spend time with them and be friends with them, so we buy food sometimes and invite them to other cities to do workshops,” Kasia Sklouda, a participant in the project, told The Local.

While eating lunch, Hojat, who lives on a different floor of Jamiat’s building, joined us. Our conversation was a mix of English, Danish, Arabic and Persian.

Both men say they fled Iran on an 18-day journey to Denmark, escaping political oppression for joining opposition movements. They say that returning to Iran is not option for them.

“When I went to court, my lawyer told me if you stay one year I can [re-]open your case. But I stayed one year and it didn’t open. But I hope that in a few months I will be able to open it again,” Hojat said about his status.

Jamiar lived in a refugee camp in Aalborg before coming to Kærshovedgård. He said the Aalborg facility had better living conditions.

“Here, we have fences all around us,” he said.

“It is right, we are living here behind fences. But we are not criminals. We are good for Denmark,” Hojat said.

Jamiar, who was a hairdresser in Iran, occasionally cuts neighbours’ hair in Kærshovedgård.

“After I go out, I want to study to become a psychiatrist, I already have a diploma in humanities from Iran,” he said.

Jamiar and Hojat invited us for Shisha in the grounds of Kærshovedgård, close to the fences. Photo: Farah Bahgat

When I asked them how they spent their time in Kærshovedgård, Hojat said he played football with his friends and attended English classes in the camp from Monday to Friday, while Jamiar attended both English and Danish language classes.

“When we go outside we have to sign to report our attendance three days a week, Monday, Wednesday and Friday,” he said, “If I stay outside the whole month they would take out my stuff from my room and send me to court, then to prison.”

After lunch, we met the only Dane we saw at Kærshovedgård, Annette.

Annette was celebrating her boyfriend’s birthday with their baby son and her 9-year-old daughter in a room her boyfriend shares with another man. We sat on a Persian rug on the floor while Anette gave us cake and told us it is the second birthday they have celebrate in the room.

“I have gotten used to it somehow,” Annette said, “I think that once you want to follow your heart, you don’t think about all this trouble.”

“We used to visit each other a lot, now it is less because he got caught.

“They make them pay a fine but they can’t pay it because they don’t have money. We just stopped caring about the rules,” Annette said.

It is common for residents of Kærshovedgård to miss their mandatory registrations. In March, a report showed that registrations have been missed 10,057 times since 2016.

“One of the [men] who lives here is married to a Danish woman and they have a child but it doesn’t change anything,” Annette said. “It is just a whole life of waiting”.

Annette and her family made a birthday card and brought cake. Photo: Farah Bahgat

Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, assistant professor in Global Refugee Studies at Aalborg University's Department of Culture and Global Studies, told The Local in October last year that camps like Kærshovedgård are designed to psychologically coerce people to leave Denmark.

“This is a very serious situation, due in part to the very rationale behind such expulsion centres. They are built on a logic that people can be motivated to leave the country. This means that the centre's main function is to impose living conditions so intolerable that people will leave. Consequently, [the centres] are not created in a way that allows for a normal, healthy life,” Lemberg-Pedersen said.

READ ALSO: Denmark rejected asylum seekers hunger strike against 'intolerable' circumstances

As a result of the living conditions in Kærshovedgård, asylum seekers sometimes get in trouble, which the residents of Ikast can perceive as dangerous.

“Most of the people who live in this area they don’t like [the camp], because here when they don’t get money some of them would go out and steal or make troubles,” Annette said.

“So people who live around here get scared, and everyone you talk to around this place says (they) don’t like (it being) here because it is criminals who live here.”

In a report published by NGO Refugees Welcome Denmark, Michala Clante Bendixen, who heads the organisation, writes:

“In Danish prisons, an effort is made to maintain the inmates’ skills and sense of human worth, while also focusing on preparing them for life once they are released. As an inmate, you are invited to take part in activities all the time – it is the act of detention, which is the punishment. Now, they are working with asylum seekers, who have never done anything illegal – and yet the staff’s task is to make their lives as empty and unbearable as possible.”

Regardless of the conditions, Jamiar and Hojat still have hope that their cases can be reopened and that they will eventually leave Kærshovedgård.

“When I am an old man I will tell my children I was living behind the fences, but I was fighting for freedom,” Hojat said, “just staying here is fighting for freedom.”

Jamiar, Hojat and Annette requested their full names not be published.

READ ALSO: Denmark criticised for 'celebrating' plight of asylum seekers in damning report

Comments

See Also

Located near the town of Ikast, Kærshovedgård is one of Denmark’s two ‘departure centres’ (the term ‘expulsion’ is also commonly used, particularly by critics). Around 200 rejected asylum seekers are accommodated at the facility until they decide to leave.

One of the residents of Kærshovedgård, Jamiar, was waiting for us a few meters outside the gate. The security guards checked our IDs and let us in as Jamiar’s visitors. As we walked by, a few people stood around the old buildings of the facility watching us. Jamiar pointed at the buildings to our left.

Surrounded by fences within Kærshovedgård’s own periphery, “this is where people who committed crimes are kept,” he said.

Jamiar told us that Kærshovedgård’s residents go to court when they commit crimes such as stealing food or not reporting their presence in the camp when they are required to.

The residents of Kærshovedgård are adult men and women who have been permanently refused asylum and whose departure deadline has been exceeded, according to a Ministry of Immigration report.

There are different categories for residency in Kærshovedgård. Women and men live in separate buildings, while individuals who have been convicted of crimes stay in separately in buildings surrounded by more fences and surveillance cameras.

We walked a little further, to where Jamiar lives, on the second floor of one of the more modern, grey buildings. The narrow hallway has doors to more than a dozen rooms, one bathroom and one laundry room. “Please take off your shoes,” the sign on Jamiar’s door read.

'Close Kærshovedgård' stickers in Jamiar's room. Photo: Farah Bahgat

The moment we walked in the room, we could smell the Persian spices Jamiar and his roommate keep. Although they are not allowed to cook inside the camp, Jamiar explained he obtained a small stove because he could not eat the food served in the cafeteria.

“The police say we cannot make food here. We can only eat in the cafeteria and it is only Danish food. I respect Denmark but I cannot eat Danish food,” he said.

Jamiar set up the floor for us to eat the Iranian lunch he had prepared for his guests, and his roommate.

“Thank you for coming, we are happy to welcome people, now we have friends from everywhere,” he said.

The Iranian and his neighbours are used to hosting friends and volunteers from different initiatives and NGOs including the Red Cross, which has a building inside the camp where residents can read donated books and clothes and socialise with each other.

Jamiar's wall. Photo: Farah Bahgat

READ ALSO: One week after minister admitted mistakes, sick asylum seeker returns to Denmark

One initiative, the Solidarity Project, arranges visits to Kærshovedgård, as well as trips for asylum seekers to other cities in Denmark.

“Our aim is to spend time with them and be friends with them, so we buy food sometimes and invite them to other cities to do workshops,” Kasia Sklouda, a participant in the project, told The Local.

While eating lunch, Hojat, who lives on a different floor of Jamiat’s building, joined us. Our conversation was a mix of English, Danish, Arabic and Persian.

Both men say they fled Iran on an 18-day journey to Denmark, escaping political oppression for joining opposition movements. They say that returning to Iran is not option for them.

“When I went to court, my lawyer told me if you stay one year I can [re-]open your case. But I stayed one year and it didn’t open. But I hope that in a few months I will be able to open it again,” Hojat said about his status.

Jamiar lived in a refugee camp in Aalborg before coming to Kærshovedgård. He said the Aalborg facility had better living conditions.

“Here, we have fences all around us,” he said.

“It is right, we are living here behind fences. But we are not criminals. We are good for Denmark,” Hojat said.

Jamiar, who was a hairdresser in Iran, occasionally cuts neighbours’ hair in Kærshovedgård.

“After I go out, I want to study to become a psychiatrist, I already have a diploma in humanities from Iran,” he said.

Jamiar and Hojat invited us for Shisha in the grounds of Kærshovedgård, close to the fences. Photo: Farah Bahgat

When I asked them how they spent their time in Kærshovedgård, Hojat said he played football with his friends and attended English classes in the camp from Monday to Friday, while Jamiar attended both English and Danish language classes.

“When we go outside we have to sign to report our attendance three days a week, Monday, Wednesday and Friday,” he said, “If I stay outside the whole month they would take out my stuff from my room and send me to court, then to prison.”

After lunch, we met the only Dane we saw at Kærshovedgård, Annette.

Annette was celebrating her boyfriend’s birthday with their baby son and her 9-year-old daughter in a room her boyfriend shares with another man. We sat on a Persian rug on the floor while Anette gave us cake and told us it is the second birthday they have celebrate in the room.

“I have gotten used to it somehow,” Annette said, “I think that once you want to follow your heart, you don’t think about all this trouble.”

“We used to visit each other a lot, now it is less because he got caught.

“They make them pay a fine but they can’t pay it because they don’t have money. We just stopped caring about the rules,” Annette said.

It is common for residents of Kærshovedgård to miss their mandatory registrations. In March, a report showed that registrations have been missed 10,057 times since 2016.

“One of the [men] who lives here is married to a Danish woman and they have a child but it doesn’t change anything,” Annette said. “It is just a whole life of waiting”.

Annette and her family made a birthday card and brought cake. Photo: Farah Bahgat

Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, assistant professor in Global Refugee Studies at Aalborg University's Department of Culture and Global Studies, told The Local in October last year that camps like Kærshovedgård are designed to psychologically coerce people to leave Denmark.

“This is a very serious situation, due in part to the very rationale behind such expulsion centres. They are built on a logic that people can be motivated to leave the country. This means that the centre's main function is to impose living conditions so intolerable that people will leave. Consequently, [the centres] are not created in a way that allows for a normal, healthy life,” Lemberg-Pedersen said.

READ ALSO: Denmark rejected asylum seekers hunger strike against 'intolerable' circumstances

As a result of the living conditions in Kærshovedgård, asylum seekers sometimes get in trouble, which the residents of Ikast can perceive as dangerous.

“Most of the people who live in this area they don’t like [the camp], because here when they don’t get money some of them would go out and steal or make troubles,” Annette said.

“So people who live around here get scared, and everyone you talk to around this place says (they) don’t like (it being) here because it is criminals who live here.”

In a report published by NGO Refugees Welcome Denmark, Michala Clante Bendixen, who heads the organisation, writes:

“In Danish prisons, an effort is made to maintain the inmates’ skills and sense of human worth, while also focusing on preparing them for life once they are released. As an inmate, you are invited to take part in activities all the time – it is the act of detention, which is the punishment. Now, they are working with asylum seekers, who have never done anything illegal – and yet the staff’s task is to make their lives as empty and unbearable as possible.”

Regardless of the conditions, Jamiar and Hojat still have hope that their cases can be reopened and that they will eventually leave Kærshovedgård.

“When I am an old man I will tell my children I was living behind the fences, but I was fighting for freedom,” Hojat said, “just staying here is fighting for freedom.”

Jamiar, Hojat and Annette requested their full names not be published.

READ ALSO: Denmark criticised for 'celebrating' plight of asylum seekers in damning report

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.