The international school in Stockholm perfecting the art of giving

“They encourage you to take leadership over a project,” says Elia Gelabert, a native of Barcelona now living in Stockholm. “When you have an idea for a fundraising project, they don't take it and finish it themselves – they let you see it through until the end. You have to lead and drive the project by yourself."

These words are spoken like a seasoned fundraising professional, someone who’s been in the charity sector long enough to recognise and appreciate the nurturing qualities of the organisation that employs her. But Elia is not a veteran fundraiser. She's just 14 and she’s talking about her teachers’ approach at Futuraskolan, a network of 14 pre-schools and schools in Greater Stockholm for children aged up to 15.

The way in which she is allowed to take responsibility also helps her focus on which ideas are really worth pursuing, she adds, knowing that "if you're not interested in it, you're never going to finish it.”

Around 3,000 children attend Futuraskolan, which has three core values: progressiveness, energy and respect. The school also promises that every child will be given positive challenges, with a focus on opportunities to develop both ”inside and outside the classroom.”

Picasso's children

To emphasise this approach, a recent letter to students from the CEO of Futuraskolan, Tom Callahan, cited a legendary artist as inspiration: “Pablo Picasso once said, ‘The meaning of life is to find your gift, and the purpose of life is to give it away.’ So we ask of you, what will you hone and develop within yourself today, so that you can better lend your gift to the world tomorrow?”

Jonathan Matta, also 14, is another student in the process of finding his ’gift’ and who, like Elia, seems mature beyond his years. But it wasn’t always so.

“I was always late handing in my homework,” says Jonathan, whose parents moved to Sweden from Egypt. “Then my technology teacher suggested I code a website to help organise the class’s homework. I had already learned coding languages such as Python, Java and C++ in my own time. But I got a bit stuck.”

However, his teachers provided support to ensure the project didn't fall by the wayside. “They were so good at encouraging me”, Jonathan says. “I sometimes give up too easily. The Futuraskolan teachers really encouraged me to finish the project. They gave me belief and it helped me complete what turned out to be a great achievement. Lots of students use the website now!”

Jonathan Matta at Futuraskolan. Photo: Futuraskolan

Jonathan Matta at Futuraskolan. Photo: FuturaskolanAn international outlook

Elia is a leader of Futuraskolan’s Global Citizenship Program, which encourages more of the school’s staff and students to become involved in community service, both locally and internationally, in order to develop a deeper understanding of the world. She embodies Picasso's idea of finding purpose by giving to others and has been the catalyst for many of Futuraskolan’s recent fundraising drives.

Find out how Futuraskolan aims to be 'the best stepping stone for future world citizens'

“One of the things that really helped develop my perspective is studying at an international school,” Elia says. “You get different outlooks from students from many countries. This international outlook influenced me to become involved in the Global Citizenship Program. I realised there are kids in the world still having a hard time, and that made me want to do something about it.”

And Elia did do something about it. She organised an array of fundraising activities, such as bake sales and Christmas markets, raising money to fund transport to school and meals for children in the Philippines. Elia’s use of her ’gift’ made a real world difference to many children thousands of miles away.

And so did Jonathan’s. “I saw what the problem was – we had a hard time organising all our homework and assignments. So, I tried to fix that problem with the skill I had and it worked. It helped the class organise their work and become better at studying.”

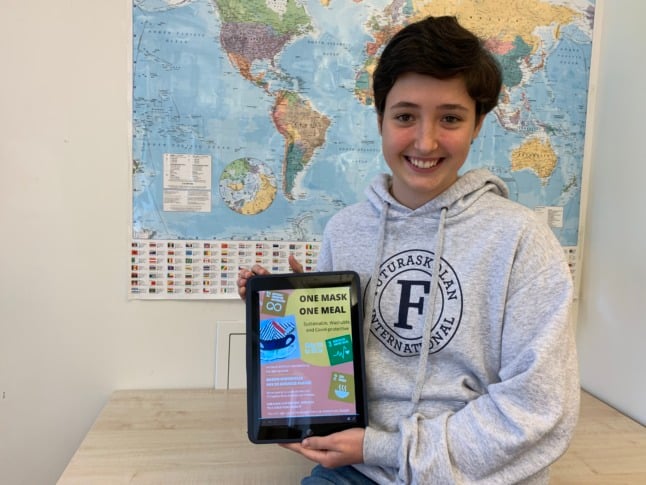

Elia Gelabert, a student and fundraiser at Futuraskolan in Stockholm. Photo: Futuraskolan

Elia Gelabert, a student and fundraiser at Futuraskolan in Stockholm. Photo: FuturaskolanThe teachers that nurture talent

Both children emphasise the huge role of the teaching staff at Futuraskolan in their achievements and the development of their respective talents.

“The teachers encourage us to ask questions and let our curiosity guide us,” Elia says. “I think that's very important because when you let curiosity guide you, you'll really know what you want to learn. We are encouraged to dig deeper into what interests us."

Jonathan adds that his teachers have "brought out my talents" through their constant support. “They made me realise that I have to keep going, that I cannot just give up when my work gets hard," he says. "They made me realise that I have a gift that I can use to help people in Egypt – I want to help Egypt with my talents in the future.”

His parents are thrilled with how Futuraskolan has helped him to develop. “In Egypt, we didn’t have a computer or even a phone, so learning digital skills was not possible,” Jonathan says. “Here at Futuraskolan, we have the technology but also the amazing teachers. My parents are so happy with the way the teaching staff here have encouraged me, supported me, but also helped me solve problems.”

Elia says her parents have been impressed with how the Futuraskolan teachers have encouraged their daughter to think globally, rather than just locally, and how they’ve inspired Elia to lead projects herself, rather than expect the teaching staff to do so.

“In my previous school, none of this would have been possible," she says. "Now it's all possible.”

This content was paid for by an advertiser and produced by The Local's Creative Studio.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.