How an original application can get you into a top university

Applying to universities or business schools can be a nerve-wracking experience when so much depends on the outcome. In a crowded and highly competitive field, what’s the best way to stand out?

By trying an unconventional application, you could give yourself a better chance to present your authentic self – and the chance to fully utilise today’s digital media. In partnership with ESCP Business School, The Local finds out more about the potential advantages of choosing to be different.

Interested in an international career in business? Find out more about ESCP Business School

Put yourself in your candidacy

Anyone hoping to study at a top university or business school needs to demonstrate personal qualities, as well as a high level of academic achievement. In many applications – for jobs as well as further studies – the personal statement is your main chance to really stand out.

Charlotte Hillig, Head of Undergraduate Studies for the ESCP Bachelor in Management (BSc), says a personal statement should “present to us the character, passions, and aspirations of the young candidates in a genuine way”. Many applicants write their letters to try to please recruiters – and in doing so they fail to reveal who they really are, she warns.

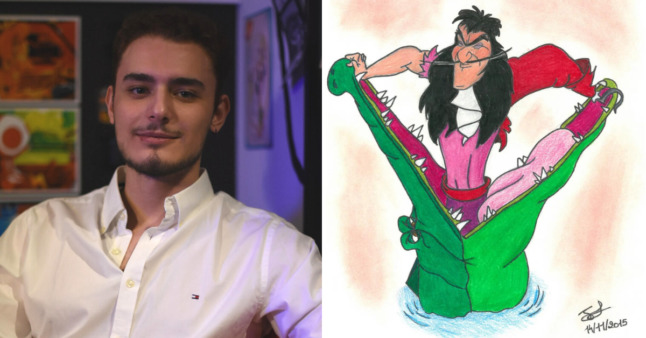

This is not a trap that Jad Zammarieh is in danger of falling into. The Lebanese student won a place on ESCP’s Bachelor in Management (BSc) after submitting one of the most original applications you could ever see.

Not content with a bold personal statement, he shared a collection of short films, poems, drawings, essays and even a video clip of a musical he wrote and directed.

“I really like to write, so I didn’t want to make a conventional application,” he says. “When a jury reads a lot of letters that look similar and then sees new ideas and a different perspective, that can make the difference.”

Jad received an answer from ESCP in under a week and was invited for an interview. “The interviewer told me he really liked my creative approach,” he recalls. “He asked me to explain a bit more about the musical I had written.”

Jad says he raised $1,500 by staging the play, which he donated to an orphanage in Lebanon. So, what is his key advice to students now preparing applications? “Put yourself in your candidacy,” he says.

Photos: Jad Zammarieh and one of his drawings

Photos: Jad Zammarieh and one of his drawingsThe digital dividend: make use of links and more

Depending on what you’re applying for (and the culture of the relevant country), you need to be careful to make your application the right length. How can you give an informative and engaging account of yourself – without any risk of it being so long that nobody wants to read it?

Fortunately, the digital world offers new ways to go about this. Jad, for example, created a blog page using Wordpress with all his creative projects and simply shared the link.

“Sometimes in a letter you need to write so many things but still be concise,” he says.

“Giving a link or even a QR code for something that can be seen online can speak a million words. We’ve all learned a lot about digital tools during the pandemic. It’s really not that complicated and it’s a good way to present yourself.”

Build your personal brand

Whatever you’re applying for – in work or study – you need a growing awareness of your personal brand. Think you don’t have one? Think again.

According to Sofia Baldissera, a career advisor at ESCP who helps students on the BSc with their career choices, everyone with any online accounts has a personal brand. She offers three key tips:

- Find out who you are – authenticity is key. Ask yourself (or your friends!) about your values, purpose and personal traits.

- Update and polish your online profiles – make sure they’re consistent with the authentic image of yourself you want to get across.

- Get networking – whether in-person or online, networking events and career fairs are another chance to let your personality shine.

Jad, who is now doing an internship at a music start-up in Berlin, says his unconventional style has also worked in other applications. It helped him through the first round of applications for an internship at a major gaming company (before applications were stopped due to the pandemic) and to secure a position on his upcoming Master’s.

Be your authentic self at ESCP

Students on ESCP’s Bachelor in Management (BSc) get to live in a different European capital during each of their three years of study – Jad studied in Paris, Turin and Berlin. Many have international backgrounds and are bilingual or multilingual.

Applications to start in September this year are open until July or August; the exact date depends on the recruiting campus according to your country of residence. The prestigious business school is seeking highly-motivated candidates with an interest in different cultures, new ways of working and diverse points of view.

What will the future hold for Jad? He would love to work in the art or film world. He also says the style of learning at ESCP gave him constant opportunities to be “creative and innovative”.

“I think that’s more important in business than other fields,” he says. “If you follow the same rules and conventions you won’t create something new.”

Find out more about applications and admissions

This content was paid for by an advertiser and produced by The Local's Creative Studio.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.